SCOTUS for law students (sponsored by Bloomberg Law): A right to remain silent, but when does it begin?

on Jun 6, 2013 at 10:50 am

Anyone who has ever watched a police drama on television knows that individuals in police custody have a right to remain silent in the face of interrogation. Actors portraying police officers may need to pull out a laminated card to read the Miranda warnings, but most viewers can recite the right to remain silent from memory.

But when does the right to remain silent begin, and, even more specifically, how does it apply to questioning that occurs before someone is actually in police custody? This important question is awaiting clarification by the Supreme Court in the case of Salinas v. Texas, which was argued on April 17.

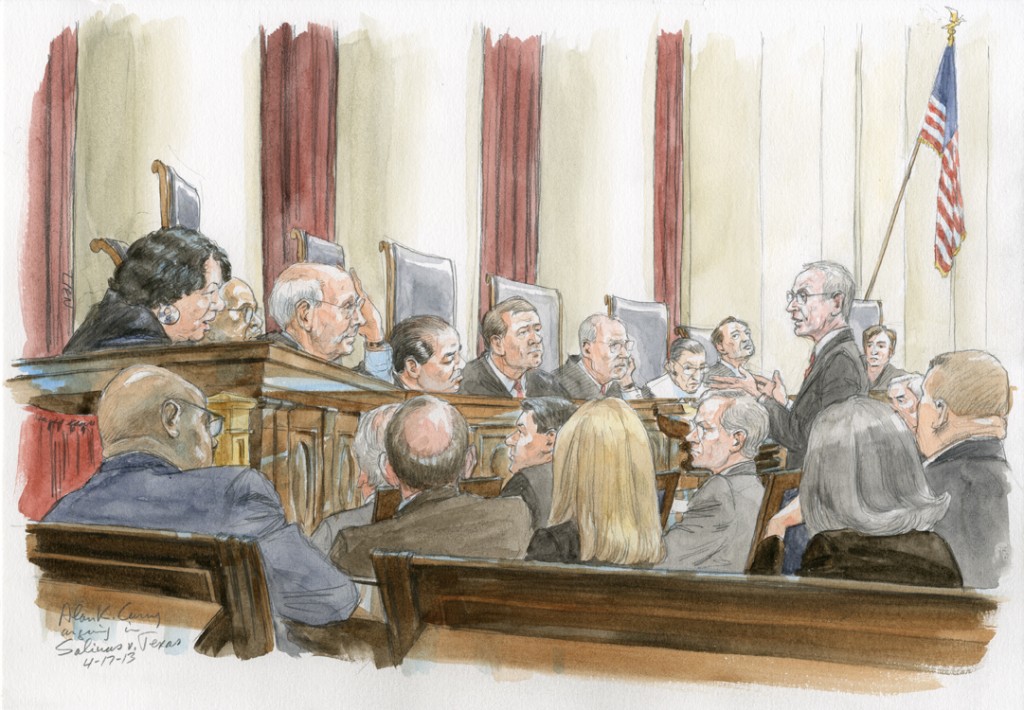

Assistant District Attorney Alan K. Curry arguing for respondent. Petitioner’s lawyer, Jeffrey L. Fisher is seated in front of lectern. (Art Lien)

At issue in the case is the meaning of the Fifth Amendment, guarantee that no one may be compelled to be a witness against himself in a criminal case, more commonly known as the right against self-incrimination. The Fifth Amendment right applies to the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The well-known warning about silence that originated in Miranda v. Arizona in 1966 is derived in part from the Fifth Amendment. But the question for the current Court is the extent to which the Fifth Amendment protects an individual before he is in custody and, therefore, before police must advise him of his right to remain silent when interrogating him.

The answer will be important for students of criminal procedure and for those interning or working in prosecutor’s offices or in criminal defense settings. Indeed, in a friend-of-the-court brief in the case, the U.S. Solicitor General, representing the interests of federal prosecutors, said the Court’s resolution of the issue “will have significant implications for the conduct of federal investigations and trials.”

The case centers on the silence by Genovevo Salinas in response to one of a number of questions he was asked by police, who had invited him to a Houston stationhouse while they were investigating a double homicide in December 1992. Salinas answered questions voluntarily for an hour but then fell silent when police asked if shotgun shells found at the crime scene would match a shotgun found at his home.

The shells eventually matched, and Salinas was charged with murder. But he had disappeared and was not captured on the murder charge for fifteen years. After a mistrial, the prosecutor at the second trial introduced evidence that Salinas remained silent when asked about the shotgun shells. The implication was that because Salinas had answered many questions but was silent about the shotgun shells, his silence suggested his guilt about the shotgun evidence.

The trial judge overruled an objection by Salinas’s lawyer that his silence should be treated as invoking his Fifth Amendment right. Salinas was convicted and sentenced to twenty years in prison.

Two Texas appeals courts ruled that the Fifth Amendment does not apply to pre-arrest, pre-Miranda silence and that it was proper to admit evidence against Salinas based on his silence. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals held that the Fifth Amendment deals only with compelled self-incrimination, which is not relevant when an individual voluntarily speaks with police prior to arrest.

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal by Salinas in part because there is disagreement among lower state and federal courts over how the right to silence works before police custody. At the oral argument, attention centered on whether an individual who is not in custody and is meeting with police voluntarily must specifically say that he is invoking the right to remain silent.

Lawyers for the Houston prosecutor and the U.S. Department of Justice told the Court that, to invoke the Fifth Amendment right, someone who is voluntarily meeting with police must at the very least say he does not wish to answer a question. It is not sufficient, the government lawyers argued, for an individual to simply remain silent, and prosecutors should be able to suggest that the silence is suggestive of guilt. Assistant to the U.S. Solicitor General Ginger Anders told the Court that it must adopt a clear, objective standard that requires an expression of an intent not to answer.

But the lawyer for Salinas called that proposed rule “ridiculous.” Stanford Law School professor Jeffrey Fisher countered that the government lawyers were urging “formalism of the absolute worst kind” and creating “a trap for the unwary,” who are conditioned to believe they have a right to remain silent without actually having to say something that triggers that right. In his view, invocation of the right to remain silent is not required during police questioning in an investigative setting in which the individual is not in custody, such that prosecutors may not use an individual’s silence in that setting as evidence of guilt.

The Justices seemed focused on how to write a workable standard that preserves effective law enforcement practices but protects the Fifth Amendment rights of individuals. The rule they write may have implications for other law enforcement settings, such as tax investigations by the Internal Revenue Service or immigration probes by federal authorities.

The case requires the Justices to navigate a labyrinth of precedents, most of which relate to when and how individuals in custody may invoke their Miranda right to remain silent. Most recently, in 2010, the Court ruled narrowly in Berghuis v. Thompkins that an individual in custody must unambiguously invoke the right to remain silent before police must stop questioning him. The ruling, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, was decided by a five-to-four vote that prompted a strong dissent by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who accused the majority of undermining Miranda principles.

The case has also attracted strong views in friend-of-the-court briefs from a broad range of interested parties. In one brief, twenty-six states argued that courts are very experienced in determining when evidence of silence is important and useful in a criminal trial. Adopting a broad rule to replace case-by-case analysis, the states argued, “would deprive courts of valuable evidence and undermine the reliability of the criminal process.”

On the other side, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers argued that allowing evidence of pre-custody silence would run counter to the advice criminal defense lawyers give to clients every day – that they should not make statements to police. The group warned that “a suspect who declines to assist the police may be deemed presumptively guilty at trial.”

A decision by the Court is expected by the end of June. The outcome may well have a significant and immediate impact on everyday law enforcement practices.

Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys work for or contribute to this blog in various capacities, is among the co-counsel to the petitioner in this case.